Venturing Insights #3 - The Power Law for Investors, Startups and Corporates

What is the Power Law? Why this is the fundamental law that drives Venture Capital? What are the implications for Investors, Startups and Corporates?

In the heart of Silicon Valley lies a creed as bold as it is transformative: the belief that most of society's problems can find resolution through technological innovation.

This creed, championed by luminaries like Vinod Khosla, hinges upon the audacity and ambition of inventors. For Khosla and others like him, progress is inexorably tied to the daring and unconventional

"All progress depends upon the unreasonable man." - George Bernard Shaw

Central to this ethos is the understanding of the Power Law, a principle that underpins much of venture capital and innovation.

Most phenomena of our lives follow the Normal Distribution

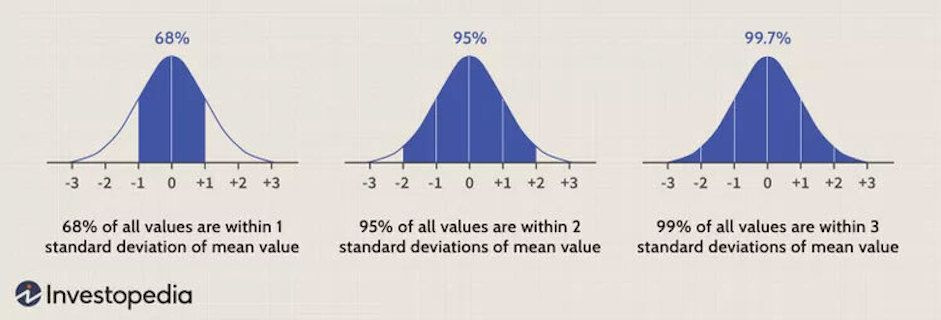

The normal distribution has several key features and properties that define it.

First, its mean (average), median (midpoint), and mode (most frequent observation) are all equal to one another. Moreover, these values all represent the peak, or highest point, of the distribution. The distribution then falls symmetrically around the mean, the width of which is defined by the standard deviation.

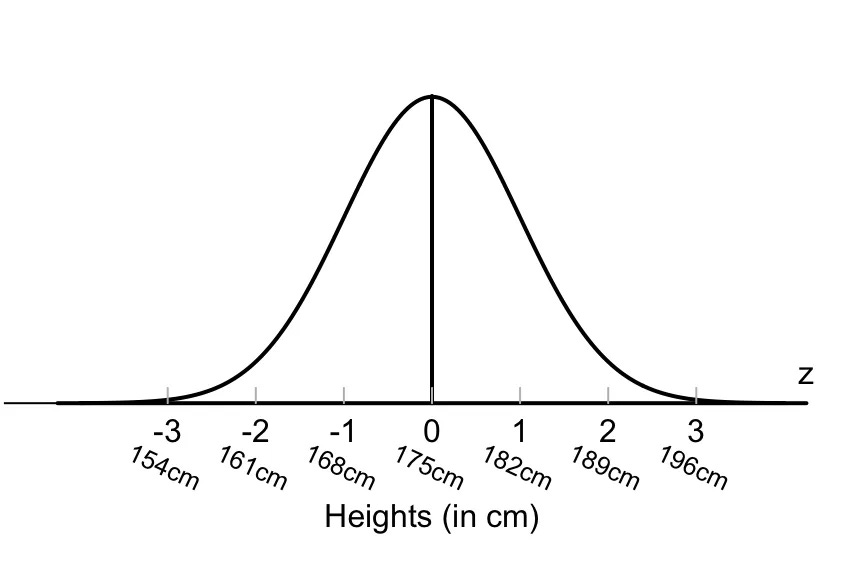

Many naturally-occurring phenomena appear to be normally-distributed. Take, for example, the distribution of the heights of human beings. The average height is found to be roughly 175 cm (5' 9"), counting both males and females.

Meanwhile, taller and shorter people exist, but with decreasing frequency in the population. According to the empirical rule, 99.7% of all people will fall with +/- three standard deviations of the mean, or between 154 cm (5' 0") and 196 cm (6' 5"). Those taller and shorter than this would be quite rare (just 0.15% of the population each).

This distribution, whether applied to the height of individuals or the performance of stocks, is characterized by its predictability and stability.

Fundamental Concepts of the Power Law

The concept of the Power Law traces its origins back to the late 19th century, emerging from the observations of Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist and sociologist.

Pareto's initial insight came from his garden, where he noticed that 20% of the pea pods produced 80% of the peas. This observation extended beyond horticulture, as Pareto recognized a similar pattern in wealth distribution, where 80% of the land in Italy was owned by just 20% of the population. This principle, later termed the Pareto Principle, laid the groundwork for what would evolve into the Power Law.

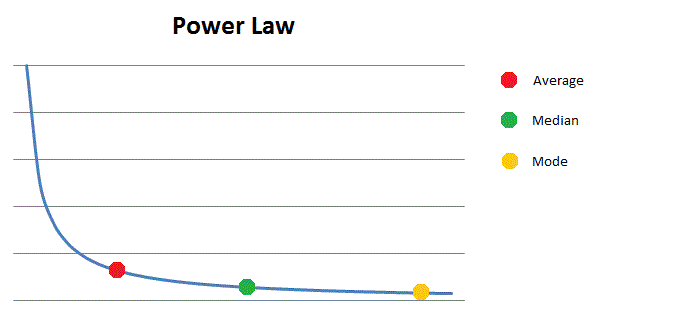

In statistics, a power law distribution is a distribution in which one variable is proportional to a power of the other.

In phenomena like wealth distribution, the Power Law manifests, showcasing how the very rich skew averages and create seismic disparities.

As a result, the mean, which is the average value calculated by summing all values and dividing by the total number of values, can be heavily influenced by these extreme values.

On the other hand, the median is the middle value of a dataset when it is arranged in ascending or descending order. Unlike the mean, the median is not affected by extreme values. Therefore, in a power law distribution where extreme values are present, the median is often a more robust measure of central tendency.

Due to the skewness caused by extreme values, the mean and median in a power law distribution are usually different.

For instance, if Jeff Bezos (Net Worth $190.5B) walks into a room of 10,000 random American people, the wealth's mean would be highly influenced, but the wealth median would remain almost the same.

Another common characteristic of the Power Law is that it drives exponential outcomes. Indeed, this distribution often exhibits exponential growth, where the success or impact of these few instances accelerates rapidly over time.

Taking again my friend Jeff, as he accumulates wealth, his chances of gaining even more riches skyrocket. Similarly, when a scientific paper receives citations, its visibility and likelihood of attracting further citations increase exponentially.

This concept transforms a world where differences are subtle into one marked by stark disparities. Once you breach this critical threshold, you must adopt a new mindset, particularly in finance, where the rules of engagement change drastically.

The Power Law in Venture Capital

In finance, this principle is particularly pronounced. While traditional markets exhibit relative stability for the majority of the time, Venture Capital operates within the realm of high-risk, high-reward opportunities.

Here, the Power Law reigns supreme, guiding investment strategies and portfolio management of VC investors.

It is widely acknowledged that a small fraction of investments will yield returns far surpassing the rest, sometimes eclipsing them collectively.

Example: Horsley Bridge is an investment company with stakes in venture funds that backed 7,000 startups between 1985 and 2014. Just 5% of the total capital deployed, generated fully 60% of all Horsey Bridge returns during this period.

To put in context, in 2018, the top-performing 5% of subindustries in S&P500 accounted for only 9% of the index performance.

Venture capitalists operate under the assumption that a single breakout success has the potential to overshadow all other investments, validating the portfolio's risk and potentially transforming fortunes overnight.

🦄 Unicorn Power Law

Coined by Aileen Lee, the term "unicorn" refers to startups whose valuations soar to $1 billion or beyond—a testament to their exceptional growth and potential.

The power law is alive and well when it comes to unicorn valuations as well.

Overall CBinsights found that:

Uber and Xiaomi account for 21.4% of the cumulative valuations of all unicorns.

The next 8 unicorns account for a further 25% of all value. (These are the decacorns sans Uber and Xiaomi, including Snapchat, Flipkart, and Palantir)

Overall these top 10 Unicorns are worth $184B, more than the next 70 combined.

Implications for Investors, Startups and Corporates

It’s clear that modern venture capital and startups ecosystem operate with the Power Law at their core. What are the main implications?

🚀 Investors needs to be ambitious

Venture Capitalists need to be ambitious: their job is to look over the horizon, to reach for high-risk, huge reward possibilities that most people believe unreachable.

Of course, investing in what is categorically impossible is a waste of resources. But the more common error, the more human one, is to invest too timidly: to back obvious ideas that others can copy and from which, consequently, it will be hard to extract profits.

Funds meticulously craft their portfolio strategies, all in pursuit of that one startup that embodies the Power Law. However, it’s worth noting that not all venture capital firms strike gold. Those that don’t experience a Power Law success in their portfolio might be grappling with a flawed strategy, subpar management, or sheer misfortune.

🌊 Startups need to chase the Blue Ocean

Entrepreneurs, on the other hand, must recognize the power of exponential growth and aim to build companies that have the potential to disrupt industries and achieve rapid scale.

By focusing on blue ocean strategies, tapping into enormous and uncontested markets, and embracing novelty and uniqueness, entrepreneurs can increase their chances of attracting venture capital funding and achieving maybe, in the future, an unicorn status.

👨🏻🔬 Corporates must exploit their Innovation Power Law

I’d like to introduce the concept of Innovation Power Law, that governs the distribution of innovation impact within an organization or industry.

Innovation Power Law suggests that only a small number of ventures or initiatives will disproportionately drive strategic and financial growth, while the majority may yield minimal impact, just like in Venture Capital Investing.

To harness the benefits of the Innovation Power Law, corporates must embrace open innovation by investing in a diverse set of ventures. While only a few of these ventures may ultimately deliver significant returns, they have the potential to greatly outweigh the initial investments and drive substantial growth for the organization.

Therefore, corporates should adopt a portfolio approach to innovation, recognizing that the potential benefits of a few successful ventures far exceed the costs of supporting a broader range of initiatives.