How to Innovate When Nothing is Defensible Anymore

From Moats to Meaning. And how is this linked to Open Innovation.

Previously on Open Road Ventures: in the last episode of Venturing Insights, we explored The Corporate Venturing Matrix 2.0 by Frederic Pampus. If you missed it, you can catch up here!

For decades, strategy revolved around defensibility. Companies were encouraged to build “moats”—technological, legal, operational, brand-related—that would make them hard to copy and easy to scale.

Moats were strategy’s favorite metaphor. Michael Porter gave us the barriers to entry. Warren Buffett spoke of economic moats. Business schools taught us how to protect advantage, not just gain it.

That logic still matters, but it’s no longer enough.

In a world shaped by AI, rapid replication, and flattened access to knowledge, the traditional sources of advantage have lost much of their defensive power. Differentiation still helps, but it doesn’t hold. Scarcity exists, but only briefly. Protection is porous.

Two recent posts made me reflect on this shift:

“Platforms, AI, and the Economics of Big Tech” and “Non c’è più niente da difendere” (“There’s Nothing Left to Defend”).

They arrive at the same conclusion: the traditional sources of competitive advantage are losing ground.

Scarcity, differentiation, proprietary technology: these used to offer protection. Today, they’re commoditized. AI can reproduce your UX. Startups can replicate your model in weeks. Even your strategy can feel like a downloadable template.

Defensibility has eroded. So what remains?

The collapse of time-based advantage

AI and global connectivity have compressed time and leveled access. What was once an edge (design, tone of voice, funnel architecture) is now short-lived.

The interface you designed this quarter? It’s next month’s Figma template.

The copy tone you crafted for your brand? A prompt away from being replicated.

The sleek funnel you optimized? Already reverse-engineered and commoditized by five competitors.

This is not hypothetical. This is happening. All the buzz with Vibe Coding is another example of this. You can build an app with no coding experience whatsoever.

Also UX is somehow replicable.

Spotify’s experience feels like Netflix’s. Google Gemini can speak convincingly enough to pass a podcast audition. Everyone can look like everyone else, and most do.

Content formats, brand languages, even product experiences blur together.

The strategic gap between first and fast follower is narrowing, fast.

There’s little left to protect.

But there is something worth projecting: meaning.

Florence, reframed

Renaissance-era Florence wasn’t without defenses. It had walls, military strategies, and even experimented with citizen militias under Machiavelli. But compared to other regional powers, it wasn’t particularly strong in military terms.

As first insightfully discussed by Sangeet Paul Choudary in his article, what made Florence resilient was something else: its symbolic centrality.

The city positioned itself as the intellectual and artistic heart of its time. Through art, architecture, and philosophy, it became a reference point for humanism itself.

Attacking Florence wasn’t just risky, it was barbarous.

To damage Florence was to position oneself against the very spirit of the Renaissance.

That cultural weight didn’t replace defense.

It amplified it—creating a form of narrative deterrence that extended far beyond walls or weapons.

Florence reminds us that in some cases, meaning can do what defense cannot.

The narrative layer of actions

That same principle now applies to companies operating in hyper-competitive markets. In environments where technology and features are quickly replicated, long-term differentiation comes less from capabilities and more from narrative weight.

We’ve seen this dynamic unfold in companies that align their actions around a shared sense of purpose.

Tesla was a case in point.

Its early advantage wasn’t just about battery tech or acceleration. It was meaning, woven into its actions.

While competitors debated standards, Tesla created its own charging network. Its Superchargers weren’t just infrastructure, they were storytelling devices. A visible signal of commitment. A promise of belonging to a larger mission.

The product experience, from design to distribution, was developed with a clear direction—and it shaped user expectations across the industry.

Over time, however, perception shifted. Sales slowed. Market sentiment fractured. The product still worked, but the way people interpreted it began to change.

What worked for a decade started to falter—not just because of BYD, but because Tesla needs a better story.

In systems where meaning plays a central role, brand perception isn’t a marketing concern, it’s a strategic one. And when that perception loses alignment, the business feels it directly.

This highlights a key idea: meaning is not a fixed asset. It evolves with context, culture, and behavior. Maintaining it requires consistency, clarity, and the ability to adapt.

P.S. Apple is another example of that.

The role of Innovation of Meaning

Today, most markets are saturated. Interfaces are intuitive. Deliveries are fast. Features are polished.

In this context, performance alone no longer differentiates.

The next competitive layer is interpretation—how people make sense of what you do and why you exist.

Roberto Verganti refers to this as the Innovation of Meaning. Rather than solving existing problems more efficiently, it reframes what problems are relevant in the first place. It reshapes the relationship between product and user.

Meaning is what people feel, expect, and believe when they interact with a product or brand.

This is the core idea behind the Innovation of Meaning framework, developed by Roberto Verganti and later refined by Dell’Era and Magistretti. It’s not about solving problems more efficiently—it’s about reframing the problem itself, and proposing new interpretations of what a product or service represents in people’s lives.

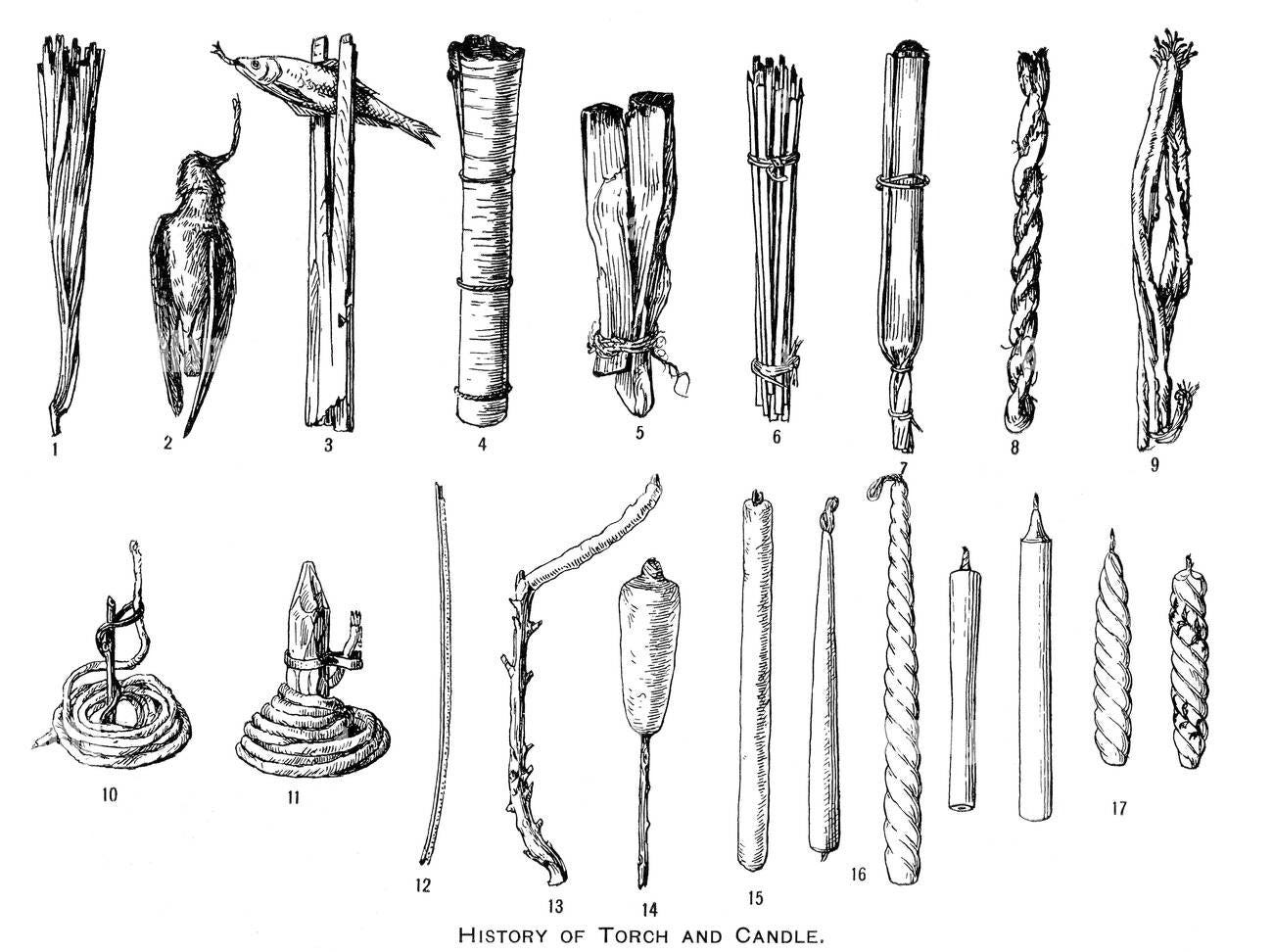

Example 1: candles

Candles weren’t reimagined to burn longer or brighter.

The innovation wasn’t functional—it was symbolic.

They now became objects of atmosphere, care, emotion. The product didn’t change. Its meaning did.

Example 2: Kartell’s Bookworm

Plastic used to mean cheap, low-end furniture.

Kartell challenged that meaning. With the Bookworm and other iconic products, plastic became a material of design: elegant, expressive, even aspirational.

Same substance, different significance.

And that shift—from usability to symbolism—unlocked entirely new market spaces and performance levels. And this is not only relevant for physical products, of course.

Open innovation as meaning-making

This shift applies directly to Open Innovation. Too often, Open Innovation teams act as feature hunters—chasing the next pilotable tech or a plug-and-play solution to a known problem.

But in a world full of similar ideas, solutions alone won’t cut it.

What’s needed is sense-making.

Startups aren’t just sources of tech. They’re partners in reframing the new meaning for corporates.

Innovation ecosystems should evolve into spaces where meaning is co-developed—not just tools.

When done well:

Open Innovation becomes a semantic engine, not a shopping mall.

Venturing teams act as curators of cultural relevance, not just deal scouts.

Startups bring fresh language, not just fresh code.

This is where Open Innovation can regain its edge: not by sourcing better tools, but by interpreting emerging signals earlier and more clearly than others.

Here’s how that might look in practice:

1. Co-create meaning, not just MVPs

Too many pilots die because they test utility without validating relevance. Instead of asking “Does it work?”, companies should ask “What does this mean in our context, and to our users?”

➡️ Use co-creation sessions with startups and lead users to explore alternate interpretations of existing trends.

➡️ Frame pilots around provocations, not just features. Ask: What tension does this touch? What narrative does this unlock?

2. Curate a narrative-aligned startup portfolio

Stop thinking in terms of verticals. Think in terms of value frames.

If you’re Patagonia, you don’t just look for sustainability tech—you look for ventures that challenge extractive thinking.

If you’re Nike, you don’t just scout performance wear—you seek startups that explore identity, belonging, and transformation.

➡️ Align your startup scouting to your brand’s evolving worldview—not just product roadmap.

➡️ Create semantic cohesion across your portfolio, so the ventures you back amplify—not dilute—your cultural stance.

3. Build distributed radar systems

Most companies rely on a small team or a few partners to filter innovation opportunities. But relevance is context-dependent—and fast-moving.

➡️ Involve cross-functional teams (CX, brand, strategy, operations) in interpreting startup value—not just in implementation.

➡️ Give internal teams structured ways to interact with the ecosystem: field immersion, reverse pitches, rotating residencies.

This turns Open Innovation into a living system of distributed interpretation, not just centralized evaluation.

4. Design “symbolic pilots”

Not every pilot needs to scale. Some should simply signal. A well-designed Open Innovation project can do what a Super Bowl ad does: express your intent to evolve.

➡️ Partner with startups on exploratory pilots designed to stretch internal mindsets and send signals to the market.

➡️ Even if the tech doesn’t scale, the meaning might—and shift how you’re perceived.

The new strategy: make meaning your advantage

If your strategy can be copied, your meaning shouldn’t be.

Florence endured not through defense, but through significance.

In innovation (especially Open Innovation) this is the shift that matters. Startups shouldn’t just add features. They should help interpret what’s next meaning for you.

Venturing teams shouldn’t just scout solutions. They should curate significance.

If your company disappeared tomorrow, what would the world lose?

If the answer isn’t clear, your strategic foundation may already be shaky.

In the age of abundance and acceleration, meaning is your real moat.

And like all moats, it requires intention, consistency, and care.

Not every company needs to be iconic. But every company needs to have a mean.

As usual, a soundtrack for you:

This is exactly why I’m on my power break. To be able to step back and see the forest through the trees again and make sense of the world and where nature based solutions fit into the hierarchy of meaning you are speaking about. I feel there is a fundamental shift happening and grasping the correct abstraction level of meaning will be key for many start-ups trying to make the world a better place. Thank you!

Meaning imo is inherently part of brand building, you want to signal to others that you “choose this brand” to further strengthen your own image. How would you distinguish meaning from branding? To me branding is the only moat that’ll be left.